Tips for winter management - Now that the ground is getting wetter, the ducks will be dibbling, picking up more earthworms from the ground. They will also be picking up more dangerous kinds of worms.

Earthworms and also snails, slugs, ants, flies and beetles are often the intermediate hosts for various internal parasites of birds; so winter is a good time to use medication. If you routinely worm the birds two to four times a year, the next time could be just before the breeding season. As well as routinely worming the birds, try to limit the opportunities for picking up parasites and diseases. Using the right feeders and drinking equipment, avoiding muddy patches during the winter, and using clean bedding all help to keep the stock healthy.

Worms in poultry - Parasitic worms are, of course, much more common in free-range poultry than in cage systems where, in theory, the birds should be parasite-free. For example, a Danish study showed that Ascaridia galli were found in 64% of free range birds, 42% of deep-littered birds and in only 5% of battery hens.

In a further study provided by Janssen Animal Health, the incidence of worm eggs in free-range flocks treated with vermifuges was recorded. 'None of the samples collected within four weeks of completion of worming was positive for worm eggs, and only two of the samples from birds wormed in the previous 5-8 weeks were positive for worm eggs - these two positive samples had the minimum detectable number of 50 eggs per gram faeces. However 45% of the samples collected 9-12 weeks after the previous worming were positive for worm eggs, and the figure rose to 81% and above for birds wormed more than 12 weeks previously and birds aged over 30 weeks that had never been wormed. These results support the current recommendations of Janssen Animal Health that free-range flocks of chickens should be wormed at intervals not exceeding three months.' It may seem that combating parasitic worms is an insuperable problem. However the benefits of the free-range system, for the well-being of the bird on both nutritional and behavioural grounds, far outweigh the disadvantages of parasitism, as long as systems are well managed. Free-range birds are happier and have better feather condition than housed birds, especially in the case of waterfowl which also need access to bathing water.

The main types of worms which affect poultry 1. Ascarides: Roundworms live in the small intestine and are particularly damaging to young birds. They cause poor food conversion, emaciation, diarrhoea and anaemia. Birds look in poor condition with ruffled plumage, and egg-laying is reduced. The period of development from egg to adult worm in 5-7 weeks. These adult worms can be seen in the droppings; they can be 3cm in length. They affect domestic fowl, guinea fowl, turkeys, ducks, and game birds.

2. Heterakis: The caecal roundworm has a similar life cycle to the large roundworm, but lives in the blind ends of the caeca, two blind-ending extensions from the gut. They affect chickens, guinea fowl, turkeys, ducks, geese, other birds.

3. Capillaria: Capillary worms (hair worms) can live in the oesophagus and crop, in the small intestine or in the caecum. They are hair-like and can hardly be seen in crop or gut contents. They can affect all types of birds but are usually most damaging in game birds. General symptoms are droopiness, weakness, and emaciation. Intestinal capillary worms cause severe inflammation, blood-stained diarrhoea, anaemia and death, especially in young birds. They affect chicken, pigeons, guinea fowl, turkeys, ducks, geese, pheasants, other birds.

4. Syngamus in poultry and Cyathostoma in geese: These gape worms make birds cough and, in extreme cases, will asphyxiate them. They affect pheasants, partridges, turkeys, guinea fowl, wild birds, chickens and, in my experience, ducks and geese.

5. Raillietina: the large tapeworm. Tapeworms in poultry are yellow-to-white, flat, segmented worms. Unlike most other parasites, they are highly variable in shape. They contract, expand, or fall apart. Large tapeworms persist for life in their host if they are not expelled. They affect domesticated fowl, chickens, turkeys, pigeons, guinea fowl 6. Davainea: The small tapeworm is common in poultry and pigeons. Organic and other free-range systems are at particular risk from infections. They usually occur in large numbers in the duodenum. Small tapeworms are so small (1.5-4 mm) that they are overlooked in post-mortem examinations. They possess only 4 to 9 segments. The head is armed with 80 to 90 small hooks, arranged in 3 to 6 rows. The suckers bear 4 to 5 rows of hooklets. Small tapeworms are considered the most pathogenic of all tapeworms in poultry. They affect domesticated fowl, chickens, turkeys, guinea fowl, pigeons.

7. Amidostomum: Gizzard worm affects water birds. The red worm damages the lining of the gizzard so the bird cannot utilise its food efficiently. In young goslings, this will cause death by starvation. It is particularly common in goslings reared on just grass, and accompanied by parents which carry the parasite. Although ducks undoubtedly carry the worms, as evidenced in wild birds, well fed domestic ducks do not appear to suffer. However, they will pick up the parasite from geese, and transfer it back. This stresses the importance of worming all the birds in a group at the same time. These worms are only seen on dissection of an infected individual. After ingestion the worms mature into sexually adult worms in about 40 days. Damage can be achieved before this.

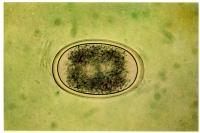

Worm Eggs If a sample of droppings is examined under the microscope by a vet, the species of worm eggs can be identified against reference pictures, available in veterinary handbooks such as Jordan and Pattison ' Poultry Diseases', WB Saunders and Company Ltd, 1996. The number of eggs will also give an indication of the level of infestation. These pictures of worm eggs have kindly been supplied by Janssen Animal Health.

Eliminating worms with Flubenvet Flubenvet is the preferred vermifuge for pheasant, partridge, chickens, geese and turkeys. The powder can be used with young birds, but the best practice is to rear youngsters on clean ground, without adults, to avoid infection. If growing birds cannot be kept separate from the adults, which may be carrying parasites, then it is essential to worm the adults before the young birds join them. Youngsters are more susceptible to the effects of worm infestation than older birds.

Flubenvet is obtainable as a white powder in drums of 240 g. It costs around £12.00 (including VAT) per unit and generally comes with a long shelf life of 2-3 years. Do make sure that the wormer is in date. Wormers can be totally useless if they have passed their use-by date. The product can be bought from your vet and also licensed retail outlets such as agricultural merchants which sell farm animal pharmaceuticals. If in difficulty, phone Interhatch at Chesterfield (01246 264646). Interhatch has a very good catalogue and will supply by mail order.

The dosage for geese and chickens is 120g on 100 kg of food (half the dosage for pheasant). This works out at 1.2g per kilo, which is easier to measure at one level teaspoonful (3.6g) per 3 kg. Check the weight of a teaspoonful on digital kitchen scales. The white powder adheres well to the pellets (better than to wheat) so just use pellets over the worming period. Don't mix it with your hand because the powder sticks to your skin. Use a table spoon. The disadvantage of Flubenvet is that you have to feed it for a week, in the food, for it to be effective. So birds which are really ill, and not eating, cannot be dosed in this way. This is less likely to happen with chickens than geese. If geese are eating grass as the main part of their diet, and will not eat pellets, then the Flubenvet powder method is also unsuitable. However, you will have to ask your vet for an alternative.

Note that withdrawal times for Flubenvet are stated on the label. The dosage for chickens is the same as that for geese. At this concentration, it is stated that there is no withdrawal time of the product for chicken eggs for human consumption. Ducks are not included in the dosage on the labelling, so a vet should be consulted if you are using this product with ducks around as well as poultry.

On heavily used ground, which has been used for poultry for many years, worming is essential. Repeat doses of the wormer may be needed because, once the birds have been treated with Flubenvet for seven days, they will again begin to pick up infection. It is possible to repeat the dosage at 3 weekly intervals (one week on medicine, 3 weeks off). Pheasant are particularly susceptible to gapeworm, and this repeated treatment is sometimes used to 'hoover up' the worms and their eggs on infested ground. It is better, of course, to avoid this situation and use land rotation and/or a low stocking density.

Flubendazole, found in Flubenvet, is effective against gapeworm Syngamus, large roundworm Ascarides and gizzard worm Amidostomum. However, tapeworm is not mentioned. I believe that flubendazole is effective against tapeworm at a certain dose, but the dosage should be obtained from a vet using a veterinary handbook. Tapeworms appear to affect chickens more than waterfowl.

Limiting the risk of infection 1. Litter management As well as rearing young birds on clean ground, always make sure that they have clean premises. Their housing should be thoroughly cleaned out and new litter used for each batch of young birds as they are moved through a rearing system, from smaller runs to larger sheds. It does not make sense to put young, vulnerable birds on infected litter.

At all stages, litter should be kept dry. The best litter, in my experience, is dust-extracted white wood shavings, or very coarse saw dust from a timber yard producing agricultural products. This is not fine sawdust, but coarse particles. Wood-waste litter can be topped up over a week and then replaced, especially if the weather is wet. In dry weather it can accumulate as long as the surface is kept clean with a new layer added as necessary. However, disease vectors such as beetles, can thrive in the litter, especially if it is damp.

All litter should finally be removed from the premises. It is not a good idea to use poultry manure on land used by poultry because their diseases and parasites are all put back. Spread the manure on land used by another type of animal, or use it as a top dressing in the garden to limit the spread of weeds. The manure is best composted first because this will also reduce the incidence of the parasites.

2. Feeders and drinkers As well as paying attention to litter management, make sure that feeders and drinkers, and the area around them, are kept clean. All-weather food hoppers cut down the amount of work, but are not always easily moved. When feeders and drinkers stay in the same location, the land around them can rapidly become overgrazed, muddy, and filthy with droppings, particularly in the winter season. Where the geese and ducks do not have access to a pool or stream, I prefer to move drinkers (buckets) on to a new location each day, Although chickens like to scratch for corn, waterfowl are definitely better fed in deep containers to limit spillage and wastage. They are not inclined to search for food like the hens, preferring to scoop up mouthfuls rather than search for grains. Spilled pellets are therefore wasted in wet weather, or become mouldy in hot weather, creating another health hazard.

At present, DEFRA's advice is to feed birds indoors to reduce contamination of their feed by wild birds. So if birds are fed indoors, use containers which limit spillage; birds should not be searching for food in dirty litter. Waterfowl can be fed outdoors in the winter when a large proportion of their diet is wheat. Feed whole wheat grains in a deep bucket of water. The birds will eat the grain under water, and it will not be contaminated by pheasant, pigeon etc.

3. Land Management Since the eggs of Ascaridia can survive on shaded ground for at least three months, birds should not be kept intensively on mainly shaded areas. Shaded, damp areas in earth runs, particularly around water and drinking troughs, can develop high levels of contamination.

Keeping grass short will help parasite control. Sunlight (ultraviolet) appears to kill worm larvae. Cultivation of the ground by harrowing is also a useful control measure. If there is a build-up of dirty material in the areas immediately outside the house, the physical removal the top 5cm of soil is advised The life cycle of worms can be broken by resting the ground between flocks. Interruption of the parasite life cycle is the best approach to control. UKROFS standards United Kingdom Register of Organic Food Standards specify, for health reasons, that runs be left empty for at least two months between batches of table poultry. Ideally, rested ground should be planted with a green crop, as birds are less likely to pick up contaminated soil when there are plenty of greens available. Other organic specifications are more stringent; resting the land reduces the need for chemicals in parasite control.

Encouraging birds to range a distance from the house, rather than congregating near the house, will assist in diluting the build-up of parasites on the pasture and in the soil.

Also, keeping poultry on free-draining land, free from excessive shading and away from damp or water-logged areas reduces the number of potential intermediate hosts (slugs, snails and beetles) which are common to the life-cycle of many parasites.

4. When birds are moved to new owner, make sure the birds have been wormed.

I always worm stock at the point of sale and notify their new owner. This is to avoid worming the bird twice, and also to make people aware that birds need to be protected from infestation. Conversely, any new stock moving on to the premises is also wormed.

Always record the date at which batches of birds were wormed, and type and dosage of wormer used. A regular worming programme at short intervals is needed if infestation is thought to be high. High infestation might be noticed by birds coughing from gape worms, for example, at only a short interval after worming.

For diagrams indicating transmission and the location of these worms in the digestive system, see Janice Houghton - Wallace 'Worming their way into your flock' in Smallholder, August 2004 All images supplied by Janssen Animal Health http://www.janssenpharmaceutica.be/jah/

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article